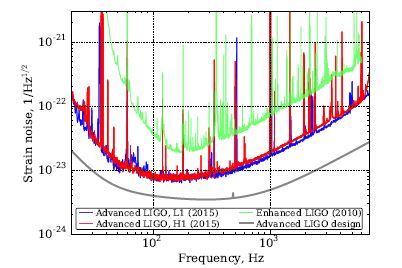

arXiv Title: The Sensitivity of the Advanced LIGO Detectors at the Beginning of Gravitational Wave Astronomy.

(Credit: LIGO)

Whether you’ve heard about the binary neutron star merger that was discovered last year or not, a new era of astronomy has opened, the multi-messenger astronomy, after scientists at LIGO and VIRGO have been able to detect both gravitational and electromagnetic waves at the same time. This is a true triumph for the scientific community, because now astronomers are able to get a glimpse of what is truly going on during and after the merger, by using the light that was emitted by this extreme energetic process.

Cmglee )

However, LIGO is having a hard time “listening” to the gravitational-wave signals it’s receiving from outer space, why? Well imagine yourself trying to listen to your favourite song in a very crowded metro station in the middle of the day. You’ll simply find it hard to concentrate on the words of the song with all noise around you, and this is exactly what the LIGO team is going through. “But noise? What noise? LIGO seems to be in the middle of nowhere! “Well, with LIGO’s sensitivity, any kind of vibration could mean mission failed, a truck outside passing through, a fly travelling near the detectors (Although having a fly inside is quite impossible because LIGO’s detectors are encapsulated inside the world’s second largest vacuum chambers, but you got my point). These are all to be taken into consideration very carefully. But no matter how careful and accurate they try to be, there’s always going to be noise from Earth itself, geophysical seismic noise, like rock sediments moving underneath the detectors for example. (See the different types of noises that LIGO has to overcome here: LIGO-NOISES ).

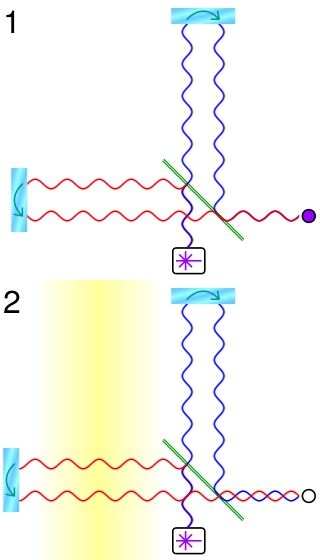

LIGO works by measuring the phase difference between two laser beams ( the red and blue parts in the figure) , which are initially in-phase, but when a gravitational wave (GW) hits the detectors ( yellow part in figure 2 ) , space-time gets distorted making one light beam travelling longer/shorter than the other, causing this phase shift. And this phase shift depends on the strength of the GW. The more this GW distorts space-time, the larger the phase shift. But how large is this phase shift? 10^-18 meters. That is 1/10000 the width of a proton! Let’s try to at least imagine the scale we’re dealing with here. The wavelength of the beams used are in the order of 10^-6 , and the phase difference to be measured is in the order of 10^-18 , this means the phase difference is 0.000000000001 times the length of the beam! This is equivalent to measuring the distance from Earth to the Sun to an accuracy less than the width of the human hair!

So, as you can see,

LIGO is extremely accurate, and with this accuracy, noise can be a real issue,

and thus LIGO has serious limitations that can be difficult to overcome as long

as the detectors are based on Earth.

What can we do when Earth isn’t the best

place for “interferometry-ing”? Easy, we take the whole lab outside of Earth to

outer space! “Wait a second? You mean we build LIGO in space?” YES! And that’s

exactly what the ESA are working on.

LISA, the Laser Interferometry Space Antenna is currently being built and is

set to launch in 2034. It’s basically formed of three spacecrafts flying in an

equilateral triangle formation. The length of the triangle will be five million

kilometers.

With merely no noise, and such large distance between the spacecrafts (compared to LIGO’s 4 Km armlength), LISA seems to be the most promising candidate to boost our new GW astronomy.

However, there are also challenges to

overcome, mainly keeping the distances between of the spacecrafts constant.

Even a change of micrometers in a length of five million kilometers long is a

problem, after all, we are trying to detect extremely miniscule change in

distances (i.e. phase shift) due to the GW. And that’s not an easy piece of

cake situation especially considering the orbits of these spacecrafts in space,

and their mutual gravitational pull, and also the force photons would exert on

the spacecrafts (photons are massless yes, but they do have a momentum).

Who knew that GW would actually be a thing today back in the 60’s when Weiss

and Thorne (who won this year’s Nobel Prize along with Barish) first speculated

that GW can be detected using Earth based interferometry. A lot of effort was put

into this huge collaboration, and half a century later, GW were finally

discovered. And the same will happen all over again until LISA is finally set

to go and leave Earth in hope to make much sensitive, accurate measurements

that will allow us to map the universe better than ever. It’s a work in

progress, and the LISA team will surely manage to overcome all the obstacles

they face, one way or another.

Leave a comment