Introduction

There isn’t much our eyes can see, nor our ears can hear. The beauty that we witness around us is only a stanza of a much bigger masterpiece. Our senses are simply bound to a tiny part of a spectrum of which many colours can never be seen, sounds left unheard and so many elements of Nature never felt. Our reality is a mere projection of these senses. Beyond them is a world we can only imagine. We learned to accept our limits but nevertheless challenged ourselves to go beyond them. And so, we gathered the questions that puzzled us, and started deciphering the language spoken by Nature, a language overruled by what our tongues can speak. Letter by letter and number by number, we have assembled this construct in our imagination. It was a world of reveries, beautiful yet not fully comprehensible. And in this world, man can only start to wonder what Nature is concealing.

For those who know this blog already, this has been a space for me to talk about my interest and humble research on quantum gravity, mainly quantum cosmology. Quantum cosmology [1] is the attempt to explain the universe on quantum scales, to tackle questions such as those concerned about the first stages of creation when the universe was in its infancy and questions about singularities. There, quantum effects come into play. So far, there is no concrete theory of quantum gravity that one can take and apply it to spacetime to explain the above questions. There are theories, which one way or another are still inconsistent, and do not yet have any experimental evidence. One thing these theories share in common though, is that whatever cosmological signature they leave for scientist to test and measure, they are a century/ies away from being technologically accessible.

This particular idea makes anyone realize that whatever research done in this field will never be tested in the researcher’s lifetime and will probably end up on arXiv or a dusty old library bookshelf. At best a Nature publication that will find some moments of glory to be eventually forgotten in the quantum gravity graveyard. This realization is a bummer, especially for someone who’s fascinated by cosmology and aimed to do further research in this field to get a good understanding of the universe. Certainly, there are still many unsolved problems in cosmology and riddles out there to solve other than the questions posed above, but the problem of quantum gravity has become somehow personal. For me, it felt as if I will forever be bound to not know such answers, that there was a technological barrier between me and the “truth”, that no matter how far I get in fundamental research, a proof will be lacking, and hence my understanding. I felt challenged and took a step back thinking whether I want to pursue this direction especially that I am now aware that my understanding of the universe will remain limited along these footsteps. I understand that this is how science works, it’s a collective collaboration towards a far fetched goal where each contributes a verse. And here I have to quote Alexandra Drennan:

How do you solve a problem that extends beyond your own lifespan? That question may be the essence of civilization. The only answer I can find is to initiate a process, to create an environment in which the solution will occur independently of yourself. But… that requires a difficult sacrifice. Letting go of your desire to bear witness, to exist at the center of the cosmos. To participate in the project of civilization is to accept death.

Alexandra Drennan – The Talos Principle

The problem of quantum gravity will most probably extend beyond my own lifespan. The process has already been initiated some 80 years ago, and the environment is there and strong. Though I find this environment to be scattered in extremely diverse groups, each hunting for their own treasure island, and being steered by mathematical consistency, rather than experimental proofs. No doubt, mathematical consistency is an important and even a main key for building a theory, but when you keep falling into loopholes for almost a century, you need to think outside the box, you need a compass to guide you where to find that consistency. I found that compass through the project goals of the VLBAI.

One Step Forward, Two Steps back

The Problem

One of the many problems of quantum gravity is, well … the quantum part of it. While the other problem is, you guessed it, gravity. Our understanding of gravity today is based on Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which, little to say, has advanced our understanding of the universe incredibly. Alas, pushing general relativity to the extreme has been futile. Blackholes and singularities are such extreme conditions where the theory collapses and the equations stop making sense anymore. On top of that, quantum mechanics becomes relevant. And that is what quantum gravity hopes to explain, a scenario where the two worlds are in play, where blackholes are no longer this mysterious objects that forbid us to know what lies beyond their event horizon and where the Big Bang is just another stage in the universe’s birth. But it has been a challenge to describe quantum mechanics and general relativity in the same framework. And to understand the reason behind this difficulty we have to split the problem into three cases:

- The problem is Gravity itself: Einstein’s theory of general relativity is incomplete and is a subclass of a bigger theory of gravity [2]. Similar to how Newtonian mechanics is a classical approximation of general relativity, the latter is an approximation of a wider theory of gravity. This is a very profound claim that can be tackled in many ways. Either we modify general relativity, or completely abandon the idea of spacetime and develop an entirely new framework. Both directions require a lot of attention to details. Many efforts have so far been done, but it remains difficult to pinpoint the right direction, mainly due to the inability to find an all-covering modification or framework. What that means is that a modification, say f(R) theories of gravity, might solve one problem, but they open up a door to another set of problems. Same goes to other frameworks of gravity such as for example entropic gravity. Not to mention the need to find an experimental motivation to any of these approaches.

- The problem is Quantum theory: The glorious success of quantum theory to explain the fundamental interactions of electromagnetism, weak and strong nuclear force eventually led to quantum field theory (QFT) and the standard model of particle physics which is considered one of the most, if not the most, elegant model in physics. Yet it also suffers from its own self predicted collapse. QFT suffers from certain divergences (UV or Ultraviolet divergences), infinites that result from certain integrals. This can be maneuvered through methods known as regularization and renormalization. However these methods do not work on gravity, loosely speaking. And that in return opened an entire research efforts to investigate if the methods and ideas used in quantum theory need to be tinkered with.

- The problem is Quantum Gravity: Einstein’s theory and the Quantum theory as they are can go well together, but one needs to figure out how. The mathematics behind quantum gravity is extremely complicated, perhaps it’s just a matter of efforts until we figure it out.

At the moment, the way to solve this problem is still blurry. Physicists are tackling it from so many directions. It is simply a really difficult scientific problem and requires much more time. Each of these cases above are extremely broad and worth a lifetime of research. For example, I illustrated the different approaches to quantum gravity in this map. Now imagine the three cases intertwined.

The SOlution

Experimental tests are as important as the foundations of the theory they try to test, and while quantum gravity is far from being established to even be tested, I found myself to be orienting towards testing the limits of our current understanding of gravity, of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Perhaps this could give us an insight as to where to look for a theory of quantum gravity as discussed in case 1 above. One way to do that is to look out into space, to see gravity, or spacetime, at work in quantum regimes near a black hole or the Big Bang, where spacetime itself becomes a quantum object. But as I have already mentioned, these cosmological attempts are technologically hindered. Here you enter the Planck scale and speak of lengths so miniscule that pushes any current observatory or satellite beyond its detection limit and sensitivity. Additional challenge in cosmology is the irreproducibility of the system. We cannot just create a blackhole in the lab and continuously test how gravity behaves around it. At some point it seems that the universe is blocking the road to uncover its mysteries. Luckily, the universe is not just the large scale structures and the gigaparsecs it extends to. The universe is also the small scale structures, from the quantum systems and processes that form the fundamental building blocks of matter, to the vacuum that creates these building blocks from nothingness, and everything in between. This realization gives us a quick insight. Build a quantum mechanical system, so small and sensitive to the smallest gravitational gradient and study the influence of gravity on that system. The question to be answered here is quite straightforward: Will this quantum system experience a gravitational effect unexplain by Einstein’s theory of general relativity? And if so, could this be hinting towards some new physics? This quantum mechanical system we are talking about can be built using atoms, where they are put into a superposition of states, a quantum property. We will talk about this in more details later. In addition, these atoms are massive, and hence this quantum system also experiences gravity. The challenge here is bipartite. One is the implementation of such an experiment, to create this superposition state and realize gravity’s effect on it . The other is to interpret whatever result you’ll get.

Matter-wave interferometry

One way to exploit the properties of a system is through a process called interferometry. The principle is as follows: Let there be a light beam through that system in one path , and another through, let’s say, pure vacuum in another path. If the two light beams started their journey at the same time under the same conditions and made to meet again at some later time to interfere, a pattern will be produced and this pattern will tell us something about the different experience they went through throughout their different journey between that system and in vacuum. See it like that: Imagine two people starting at a point A and made to run towards a point B but one through a flat field and the other along a top of a hill and down to B. When both persons meet again, you could tell who went through where by how tired they are. Here in interferometry, instead of people we are using light (and later atoms as we will see) as our reference, and instead of our flat field and the hill we have different paths (the “system” and the vacuum) along which the light experiences different potentials.

A famous interferometric test is that of Michelson and Morley. They split a light source into two beams of light where one traverses through the sought-for Ether, and the other longitudinal to it. The hypothesis then was that one beam will arrive at the other end later than the other beam due to the motion of light through the Ether. And this elapsed time difference can be detected through the interference pattern the two beams produce after recombination. But no pattern was observed, and the Ether was never found, nor will it ever be because it was never there. This is an example of light intereferometry, the manipulation of light through beam splitters and mirrors to obtain an interference signal that reveals the property of a system under study, where that property was whether the Ether is present or not.

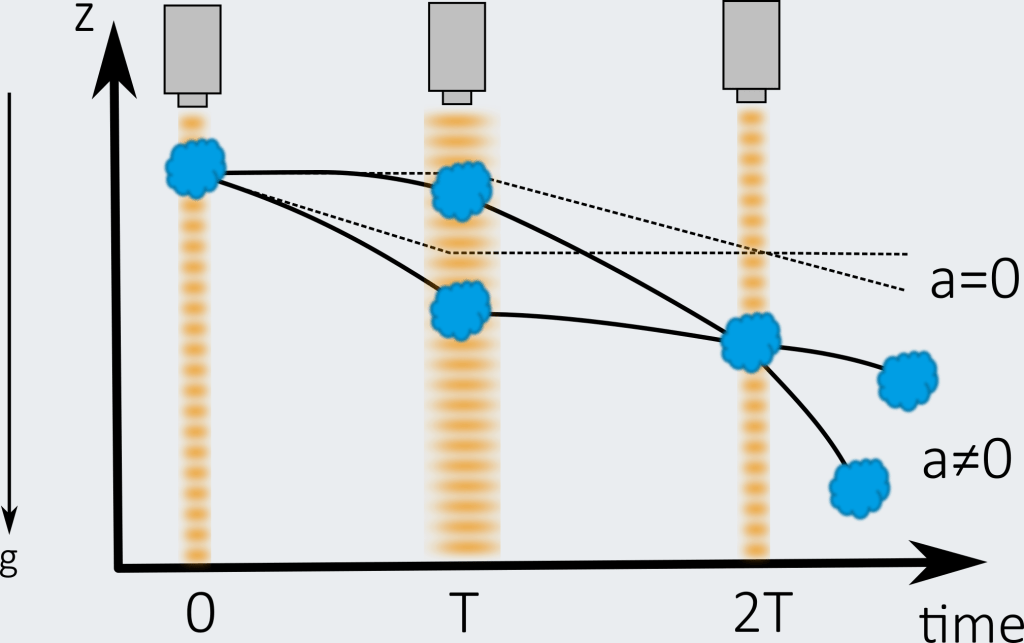

Atoms, similarly to electromagnetic waves and light, can also be guided and let to interfere, and this atomic interferometry can be implemented by exploiting the wave-particle duality of an atom, another quantum property. Cool an atom to a millionth or even a billionth of a kelvin, just above absolute zero, and the wavelength of the atom will be significant. It’s all in the physics of the DeBroglie equation, where the wavelength of this atom (known as the DeBroglie wavelength) is inversely proportional to its momentum. At this point, atoms behave as waves and we call them matter-waves, and they can be split, redirected and combined in an interferometric scheme, exactly how we use mirrors and beamsplitters (BS) to manipulate light. The only difference here is that these mirrors and beamsplitters are now made of light! Let me explain. Just as light-wave interferometry requires mirrors and BS which are made of matter to manipulate light, matter-wave interferometry on the other hand, requires light for that task, more precisely, laser beams. Shoot a laser beam onto an ensemble of atoms, and you enter a domain of “atom-light interaction” where the beam can manipulate the ensemble, redirecting and guiding its motion in space, exciting it, causing it to oscillate between states, cooling and trapping it and many other phenomena. It carries one main and crucial advantage in comparison to light-wave interferometery when it comes to our challenge, and that is that atoms have a rest mass, meaning their interaction with the gravitational field is much more significant and evident unlike the massless photons. For now, what you need to know is that matter-wave interferometry is an existing experimental method, one which can be used to measure extremely accurate details of a system and is the basic principle behind the VLBAI which I shall now introduce.

Very Large baseline atom interferometer

The Very Large Baseline Atom Interferometery facility (VLBAI for short), located at HITech in Hannover, Germany, is a 16 meter facility dedicated to perform matter-wave interferometry. The ultimate goal here is to resolve effects that cannot be observed on short baseline interferometries. One of these effects that I will be concerned about here, and as motivated above, is that of gravity on matter-waves. In general, from the interference pattern observed, an important quantity, the phase shift of the waves, can be extracted. In our case, this phase shift contains valuable information about this gravity/matter-wave coupled system under study. The phase shift of the matter waves falling in a gravitational field is proportional to the square of the time they fall before recombining and interfering. So, the longer the free fall time, the larger the phase shift, and the more resolved and accurate the observation is which explains why we would need a 16m tower to do the job. With a long baseline, the VLBAI allows around 2.8 seconds of free fall time which seems to be a short amount of time, but actually it is not! 2.8 seconds are more than enough to study the behaviour of the atomic system and detect a noticeable phase shift.

The sensitivity that we are talking about here makes this phase shift measurement prone to external effects. Vibrations, gravity gradients due to surrounding masses, even magnetic fields, they all affect the phase shift measurement which we want to avoid. For these reasons, the VLBAI is shielded from these magnetic fields and wrapped with a 10 m solenoid coil around the baseline to provide a well-defined magnetic field [3]. A seismic attenuator, a device (seen at the bottom of the image) is installed to the baseline to reduce vibrational noise. With all this in set, the VLBAI is ready for an unprecedented sensitivity in phase shift measurements. But what are we exactly hoping to realize from this phase shift and how can it help us push our current knowledge of gravity? To answer these questions we need to dig in deeper on what this quantum system is and how do we arrive to it. After that we need to explain how gravity influences the matter-wave and how we can exploit this influence to search for new physics. I will close this part here and tackle these questions in Part II where we take a look on the sophistication of such an experiment, the beautiful intricate details, and the many laser frequencies we need to talk to the atoms to do the job and tell us about what gravity really is. It will indeed be a grand symphony.. in the optical frequency range. Stayed tuned!

[1]: I can recommend this great book by Calcagni.

[2]: Also another well written book by Faraoni.

[3]: E. Wodey et al. Review of Scientific Instruments 91, 035117 (2020)

Leave a comment